|

With the help of outside donors, principally the United States Agency for International Development, the institute was patched up enough by 2000 to admit its first full class in a decade. "That class of 840 was largely kids who had been combatants, who had lost their parents, or had been displaced by the war," Mr. Jackolli said. "They were thirsty for the skills to make a living."

About 55 teachers and aides taught the 840 freshmen and sophomores that year. Day students paid $20 a semester; boarders $250. They learned accounting, engineering, business, home economics, secretarial work, auto mechanics, agricultural sciences, carpentry, masonry and plumbing -- skills needed to rebuild the country.

Then came Wednesday morning, April 3, 2002. At about 11 a.m., the rebel Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy attacked Kakata and raided the institute, where they raped and kidnapped students, Liberia's Defense Ministry says. Government forces retook Kakata the next day, but the students were too terrorized to return that spring.

School started again last September. But the government did not continue paying the teachers and administrators their salaries of $20 to $40 a month, and the war kept many students away or robbed them of their means to pay tuition. Only a handful remained for classes this spring. The campus is deserted now except for staff members who saved it and a steady stream of refugees.

Last Tuesday, Mr. Walker and six of his colleagues took a visitor on a stroll around the campus, explaining its history.

C. D. B. King, Liberia's 16th president, visited Tuskegee Institute, the black college in Alabama, in the late 1920's, and decided he wanted to transplant it to Africa. He hired Robert Robinson Taylor, the first black graduate of M.I.T., to design the campus and a course of instruction. A white man from Georgia, James L. Sibley, was the first principal. Though he died of malaria on June 28, 1929, the coeducational school was by then in business, backed by the Phelps-Stokes Fund, an American philanthropy, and Firestone Rubber, which controlled a nearby million-acre plantation.

"B.W.I. played a very important role in building this country," Mr. Walker said. Those who built "its roads, its bridges, its public works, its banks," he added, "graduated from here."

"Before the war, we had students from all over West Africa, and faculty from all over the world."

Now, he said, "Students come here every day asking if they can enroll -- they are thirsty. But what happens to them when they graduate? Every industry in this country is closed."

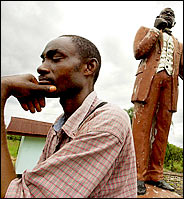

Jacob B. Swee, 39, the head of the institute's agriculture department, said a generation had been lost to war in Liberia. "The young people who should be taking over from us are lying in the bush holding a gun or sitting in a refugee camp," he said.

The institute will reopen as soon as possible, perhaps this winter if Mr. Jackolli can raise the money to buy books and pay teachers. It will take years to restore the campus. Bids submitted in 1999 for that job ranged from $18 million to $25 million.

| |